Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 25, 2022

Freytag’s Pyramid: Understand the Shape of Tragic Drama

About the author

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

More about the Reedsy Editorial Team →Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

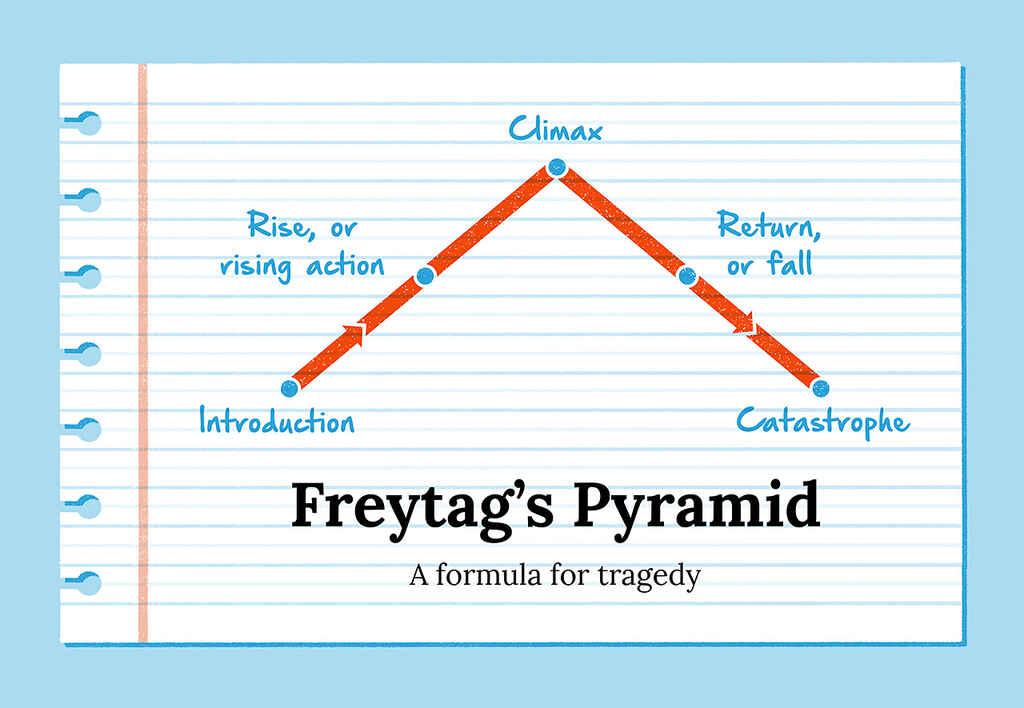

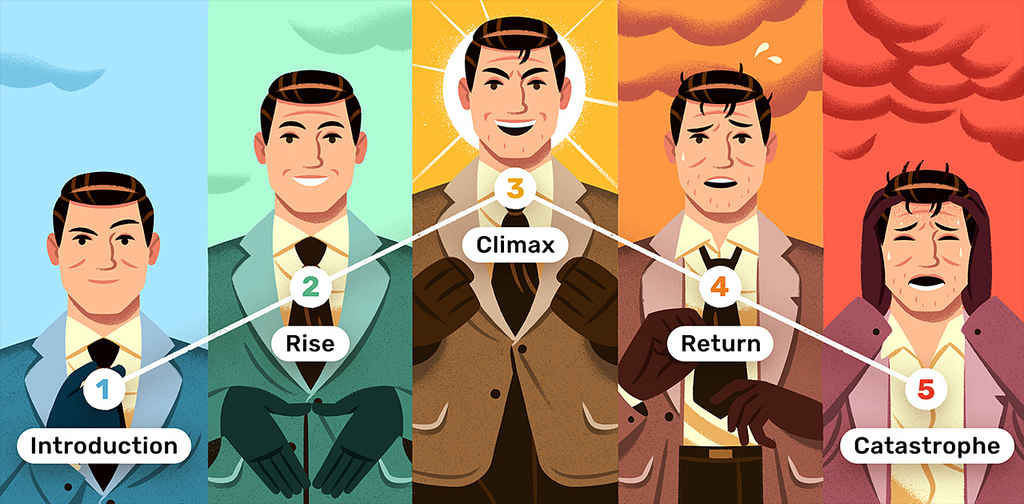

View profile →Freytag’s pyramid is a dramatic structure introduced by German 19th-century writer Gustav Freytag. The pyramid, also known as "Freytag’s triangle", is a straightforward way of organizing a tragic narrative into a beginning, middle, and ending, and is comprised of five distinct parts; introduction, rise, climax, return, and catastrophe.

Read on to discover the acts that make up Freytag’s pyramid, and pay close attention as we apply each to Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman. You’ll be a Freytag expert in no time.

What is Freytag’s Pyramid?

Freytag was interested in classical Greek tragedy and Shakespearean drama, and devised his pyramid by observing their structural patterns.

Make no mistake: Freytag’s pyramid is not a one-size-fits-all structure. It identifies story elements that are common to classical and Shakespearean tragedies, including a revelation or plot twist that changes everything — resulting in catastrophe for the hero.

Q: Can I break traditional story structure rules and still write a good book?

Suggested answer

The quick answer to this is yes!

The longer answer is that, in order to break the rules of traditional story structure, you must first understand them. Authors who are successful at going completely outside of the 'norm' in storytelling and writing really know their stuff. They understand why the 'rules' are in place, and then they work hard to go against them in a meaningful, intentional, and acceptable way. If you look at experimental literary fiction, for example, you'll see a lot fewer examples than, say, the typical commercial fiction novel. In commercial fiction, there are certain expectations in terms of style, voice, tropes, structure, etc. Readers go to these types of novels to have their reading desires and expectations fulfilled. But that doesn't mean you can't surprise them every now and again.

The great thing about writing fiction is that you can do whatever you want--the sky is the limit. Structure, style, etc. can be played around with, but it must be exquisitely executed. And to achieve that, you must first know the rules like the back of your hand and master them.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Breaking the traditional story structure is best done after you have a few books under your belt and are a seasoned author, especially if you are seeking a traditional publisher. There is enough risk for publishers to take a chance on a new author without the added risk of trying to push something that is out of the box. There are many people in the publishing chain of approval, and trying to sell the idea to the bulk of a publishing staff can be challenging if the author has no track record of sales to speak of.

When starting out, it really is a good idea to "play by the rules" if and when possible. That doesn't mean your book will not be "good" if you break the rules, but it's risky. Because the reality is that not all "good" books get book deals. This business is very subjective, and publishers run for-profit businesses, and they want and expect to make money on their books. Unfortunately, every decision regarding books that get chosen for publication is not based on artistic merit alone.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

As a result, the pyramid is less applicable to non-tragic narratives in which the protagonist usually wins out in some way, or when writing more upbeat genres like comedy. Freytag’s five-act framework is notably one of many approaches that writers can use to create a complete and satisfying story for readers.

A note before we dive in: despite the fact that the pyramid was originally based on drama, Freytag’s ideas are ultimately about storytelling, so they can also apply to both fiction and non-fiction writing — books, plays, TV, film, novels, memoirs, and short stories alike.

Want to know what kind of characters populate Freytag's Pyramid? Check out this post on tragic heroes to find out.

The 5 stages of Freytag’s pyramid

Though you may encounter explanations of the pyramid that identify 7 elements, Freytag’s original narrative arc only refers to 5 key acts:

- Introduction: Establish the characters and stakes.

- Rise, or rising action: Things seem to be on the up.

- Climax: The world is turned upside-down.

- Return, or fall: We’re heading for tragedy.

- Catastrophe: The inevitable becomes true.

Let’s break down what each of Freytag’s acts entails, from hopeful beginnings, to fraught middle, to a tragic ending. To demonstrate how every act applies to an actual story, we’ve followed them with a Death of a Salesman example. If you aren’t familiar with this classic play, consider this your spoiler warning (and your trigger warning for mention of suicide)!

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

1: Introduction

This beginning act is designed to orient the reader and set the story in motion. It asks and answers the question “where am I?” followed by “what is happening?”. As the reader (or audience), you are brought into a new environment — so the first act needs to establish the circumstances in which the characters find themselves, and introduce readers to the world and the way htings are normally.

Q: What makes a compelling first chapter in a novel?

Suggested answer

The first chapter of any novel is so, so important. It's where the story is set up so that readers can get a taste of what they're in for over the next 8-12 hours. However, there is a multitude of elements that go into successful first chapters, and they must be expertly woven together to make it compelling. By the end of the first chapter, it comes down to one thing: if the reader isn't hooked, they likely won't continue. And they need three things to keep them interested.

- Curiosity

- Tension

- Emotion

The sooner these things become apparent in the pages, the better. Readers want to feel emotionally connected to the main character so that they can empathize with them, feel like they intimately know them, and root for them to reach their goal. They want to care about what happens to them. If there's tension, readers will worry about them and be curious about how it's going to play out. And when readers are curious, that means they're theorizing about what might happen. If they're theorizing, they're engaged in the story. Their brains feel like they're actively participating in figuring things out--and that's what makes them feel compelled to keep turning those pages.

My favourite novels aren't the ones that open with a beautiful sunrise or a description of the surroundings or backstory or having a character wake up. These are cliché in today's publishing landscape. Instead, they have opening lines or paragraphs that evoke such strong curiosity in me, something shocking or surprising or unexpected, that I'm hooked right from the start. These are the novels that hold my attention not just through the first chapter, but through all of them. The authors make sure there's curiosity, tension, and emotion present, along with other elements, such as a hint about the protagonist's internal conflict and flaws, an idea about goals and stakes, their desires, an imbalance of power, more showing than telling, etc. that contribute to my brain's need to feel engaged and interested.

So, it's not just about having all the elements that go into writing an exceptional novel. It's the art of weaving them all together in a style and voice that's intriguing and engaging from the very first page. Readers of fiction want to be entertained, so it's your job as the writer to make that promise and follow through with it by capturing their attention as soon as possible in the first chapter and not letting go until the very last page.

Kathleen is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Starting with a strong opening line that is intriguing will help pull the reader into the narrative.

"Where is Papa going with that axe?" is the opening line of Charlotte's Web. We open with intrigue, and in the middle of the action of the story.

Then you want to have a strong build-up to the inciting incident, which should come at about 12,00-13,000 words into the story.

You want your main character to be likable and interesting to the reader.

You want to leave any backstory details for later on and keep the action of your opening scene continuous and going strong.

Then, if possible, you want to end this chapter with the promise of more "trouble" to come or an unanswered question regarding the trouble at hand, or at the very least, some ruffled feathers regarding your main character. There needs to be trouble brewing soon, and discomfort felt by your hero.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Some writers subdivide the first act into the ‘exposition’ and the ‘inciting incident’; these correspond to the first and second questions above.

The exposition provides information about the characters and the relationships between them, as well as any backstory required to understand the stakes of the plot. Think the introductory scenes of Macbeth, where we are introduced to the key players in the aftermath of a great military victory, and learn about their relationships to one another.

The inciting incident is the first point of deviation from the norm — an event, discovery, or new idea that triggers change. Returning to Macbeth, this would be when the witches share their prophecy with Macbeth, setting him off on a new course of action.

Example: Meet Willy Loman

The play begins on an evening in 1949 when aged salesman Willy Loman returns to his Brooklyn home. In a conversation with Linda, his wife, it emerges that his once-promising career is failing. Their adult sons, Happy and Biff, are asleep, and the audience witnesses their parents’ anxieties about Biff’s unstable lifestyle.

The inciting incident arrives when Linda suggests that Willy speaks to his boss about his difficulties, to secure a local job that won’t require him to drive far anymore.

Learn to establish your characters with our free 10-day course:

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

2. Rise, or rising action

The second act of Freytag’s pyramid is an in-between period of rising tension and escalating plot complexity. The events kickstarted by the inciting incident now pick up momentum as Act 2 reveals what’s at stake for the characters while offering a false promise of hope: a light at the end of the tunnel. The stakes, tension, and hope manifest as suspense, anxiety, or new insights into your character.

In Antigone, the rising action is the period where tragic heroine Antigone struggles to secure an honorable burial for her brother, against her uncle’s wishes. Despite hope her sister may help, she is ultimately unwilling, and Antigone’s desperation grows.

If we visualize the introduction as the moment the snowball takes form, the rise is the real snowball effect: the growing, spiraling acceleration towards a climax.

Q: What are the signs that the middle of my story isn't working?

Suggested answer

People tend to rush through the middle because the beginning and ends is more exciting to focus on haha. We can often see signs of this if it feels as though there's either a lot of recap or constant going from scene to scene (this happened, then this, then this).

We still want tension and emotional moments in the middle; it's good to break up the transitions with these.

One more trick I suggest is asking yourself "What is the goal of this scene/this moment?" or "What am I hoping this does for the reader or plot?" We still need to be thinking of the internal and external motivations as we move through the middle chunk.

Val is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When there are no more problems to be solved or there is not enough conflict and tension in the middle to keep readers reading. There must be plenty of conflict and tension and the major problems of the story should not be resolved until the end of the book.

If there is no subplot and the pace slows. Another way is to have someone else look over your book and give you honest feedback on the weak areas that concern you.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: Biff and Happy’s growing concerns

Several minor scenes make up the rising action part of the play, but briefly:

- Biff and Happy discuss their restless disillusionment with their present lives and their father’s increasingly irresponsible night driving.

- Biff and Happy decry their father’s helplessness to their mother, but she defends him, explaining their financial hardships and confessing that Willy has attempted suicide.

3. Climax

In the tragedy model, the climax isn’t the big confrontation at the end — Frodo at Mt Doom, Superman facing off against Lex Luther — but a point of no return. It’s like reaching the top of a rollercoaster — the illusion of control is lost as gravity takes over. It’s a turning point, and it changes everything.

Sometimes, the climax is a highly dramatic event, like Medea killing her children. Other times, it takes the form of an inner realization, like a new awareness of one’s cowardice and a resulting determination to face one’s fears. Afterward, the plot continues to progress, but it does so in light of the climax and its revelations.

In tragedy, the climax is the point where the plot begins to unravel, with everything now taking a turn for the worse.

Example: Willy reaches breaking point

With the knowledge that Willy has suicidal thoughts, the audience understands that, should the family’s bad luck continue, Willy will be tempted by the idea of a life insurance payout rescuing his family.

Q: How can authors effectively build tension leading up to the climax?

Suggested answer

Well, the main method is to up the stakes as you go along. The more it matters emotionally to the characters and externally to their circumstances and the world around them, the more important that climax becomes. Every time you increase the stakes, the anticipation of readers goes up surrounding the climax and what might result. The final confrontation between hero(es) and villain becomes and edge-of-the-seat affair.

If you struggle with this, the technique I recommend is to examine the plot questions asked and answered. All plots are effectively a series of questions asked and answered. When you ask and how soon you answer is part of building tensions. Some questions carry over several scenes, some are answered right away. Some last whole chapters or several chapters. Some are asked at the beginning and not answered until the end, like the main driving core quest question of will good conquer evil? Will the protagonist get what he or she wants or needs? Will the villain prevail?

Make sure you are answering the questions you ask in appropriate places. Yes, you may want to set up a sequel and leave a few things hanging but the trick is to pick the right questions. The rest need to be answered, and figuring out which questions depend upon that climax and asking more and more of them as you lead up to it is a really great way to increase suspense and anticipation and lend that sense of urgency to the climax that keeps readers turning pages and dying to know what happens.

Bryan thomas is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Stakes need to be continually raised as the story builds to a climax. The problem[s] should be getting more and more difficult until the climax is reached.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Subtle foreshadowing is a solid way to build tension. Hinting at what's to come can prime the reader for the climax without revealing exactly what's coming—just that something is coming.

Well-written, lower-level conflicts between characters is another effective tool to build tension: short arguments, occasional emotional blow-ups, etc. These are, in effect, a kind of foreshadowing themselves, setting the reader up for the finale, whatever it may be.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Tension reaches a new peak when Willy asks his young boss for a job in New York. The boss refuses and fires him, leaving Willy betrayed and angry. From this point onward, the plot spirals out of the characters’ control, leading them downward on their way to catastrophe.

4. Return, or fall

Once the protagonist crosses the point of no return, the plot speeds forward with a growing sense of inevitability. This is tragedy, so the audience always feels a sense of imminent disaster. In the return phase, also known as the reversal, we are presented with moments of tension as in Act 2, but this time tension hits harder, because of everything that has preceded it.

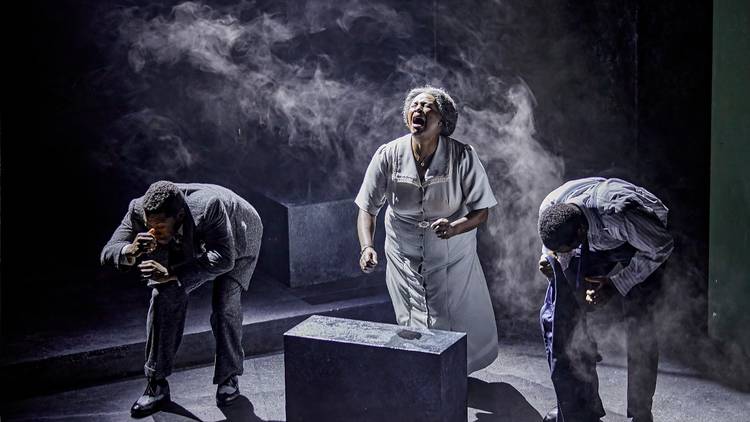

Theatrical director Ivo van Hove, discussing his production of Miller’s A View From the Bridge, used a description that perfectly captured the audience’s transfixed and helpless state in Act 4: “It's as if you see two cars, and they are driving towards each other, and you know what will happen.” In other words, Act 4 is when the inevitability of tragedy becomes all too clear, and the tension becomes unbearable.

Q: How can writers incorporate popular story models like The Hero's Journey and Save the Cat while maintaining originality and creativity in their writing?

Suggested answer

Saving the cat can come into play in many forms. At the end of the day, readers want to root for likable heroes. If you make your main character sympathetic in some way, that sort of ticks the "saving the cat" box off nicely.

A journey can comprise so many forms. It can be a literal journey Dorothy takes from Kansas to Oz and then back again in The Wizard of Oz, or it can be an inner journey of deciding to take charge of his life and not let others make his decisions for him, as we see with Macon Leary in the book The Accidental Tourist.

As long as your "save the cat" moment and "hero's journey" uses unique ideas that have not become cliché, you should be fine.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: The truth revealed

Like Act 2, the return or fall phase of Freytag’s pyramid consists of several scenes of tension. One takes place when the Lomans go out for dinner: Willy confesses that he’s lost his job, and Biff — who has failed to secure a deal his father was optimistic about — tries to relate this news in a painless way. A flashback reveals young Biff discovering his father’s affair, casting their difficult relationship in a new, tragic light. Finally, Biff and Willy clash in a furious argument over Biff’s professional failure.

5: Catastrophe

Catastrophe takes place when the character is finally brought to their lowest point. Like the climax, catastrophe may take many forms: a character could die, be financially ruined, or lose everyone’s respect. Everything the character has feared from Act 1 comes true. Think Oedipus’ blinding, or Lennie’s death in Of Mice and Men. Whatever the catastrophe is, it’s a forceful conclusion to the build-up of tension, the moment everything comes crashing down.

Though Freytag’s original analysis didn’t discuss denouements, people sometimes treat these as the seventh element of his pyramid. A denouement brings resolution, settling all remaining questions and tidying up loose elements of the narrative. It can also suggest how the story moves onward after tragedy.

Example: The Lomans get the money, but at what cost?

Catastrophe hits Death of a Salesman when Willy intentionally kills himself in a car wreck, allowing his family to claim a $20,000 insurance payout. His death does not come as a surprise, but it still hits hard, forcefully shattering his family’s chances of happiness. In a pattern that recurs in tragedies, the Lomans get what they want, but at a great and irreversible cost.

A denouement takes place at the very end of the play, after Willy’s funeral. The audience finds out what his sons plan to do now, and, amidst her grief, Linda provides an unlikely sense of resolution as she utters, “We’re free…” The denouement makes explicit something we may have realized at the moment of catastrophe: that her husband’s tragic arc is also her own; that she will have to live with the consequences of her actions.

When should writers use Freytag’s pyramid?

If you’re wondering why an author would choose to use Freytag as a model, or are an author yourself considering it, here are three instances when you might wish to choose Freytag’s pyramid as a story structure.

To create empathy in the reader

As a linear dramatic structure, Freytag’s pyramid operates subliminally. You aren’t thinking about act breaks and story beats when you read a novel, but you’re under its structure's spell anyway. A narrative that follows this pyramid’s flow guides the reader towards understanding what’s at stake for the characters.

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

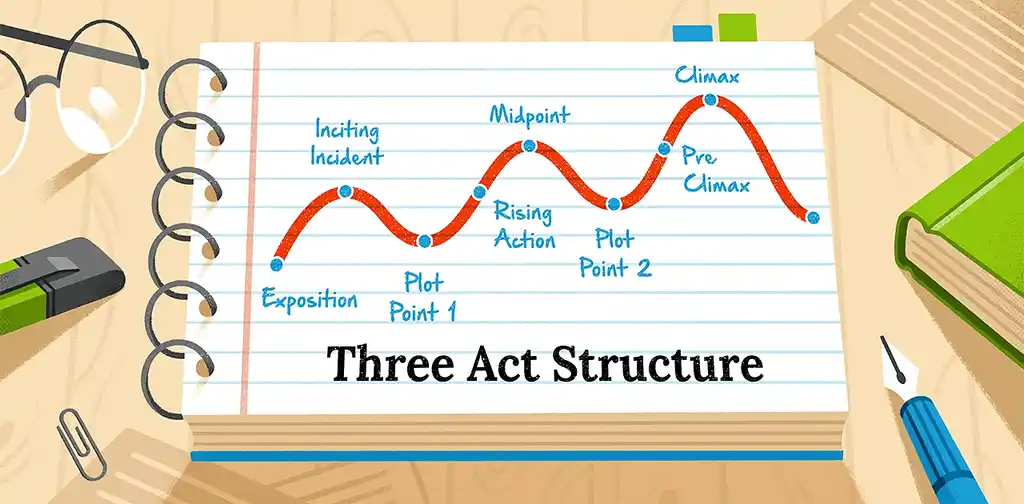

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

When I work with new writers struggling about where various story beats go, I typically refer them two The Hero's Journey by Joseph Cambell, and Save the Cat Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody. Both of these describe slightly different elements of what is included in a story.

Now, sometimes writers can get too caught up in fitting their story exactly into these story templates. But that's all they are; templates. An analogy I like to use with authors is that there are cooks, and there are chefs.

Cooks follow the recipe (story structure) exactly, never deviating, and while it can produce good dishes, there sometimes is a lack of creativity within. Chefs, on the other hand, also follow the recipe, but they also know it well enough to deviate from it. Add their own flair, flourish, and spices. By the end, the story is recognizable but their unique take on it.

You have to know the rules to break them, so for newer authors I work with, having them break down their story into the various story beats and plug them in to the two templates above can help them see where each story element fits, and maybe where a story element needs to be added or elevated.

Sean is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

You wouldn’t appreciate a climax if you didn't understand its impact on the status quo, just as you wouldn’t even recognize rising action if you didn’t know what was new. You need to understand a character's experiences to empathize with them. This pyramid structure maps the story into a pattern all humans are familiar with: desperately wanting something, only to be denied it.

When telling stories that center around human flaws

If the beating heart of your story is the strengths, weaknesses, and internal conflict of your characters, Freytag’s pyramid is a great framework within which to draw out and examine these elements. The pyramid shows every step of our fatally flawed tragic hero’s journey, from the status quo when their flaws are still (just about) under control, to the point of no return when they finally get the better of them, to their ultimate demise. If you’re writing an intense character study, Freytag is a good roadmap.

For downbeat endings that pack a punch

The beauty of a distinct dramatic structure like Freytag’s pyramid is that the framework is designed to make stories satisfying. When done right, following Freytag’s pyramid when writing means readers will understand the purpose of each scene in relation to where it is in the story (e.g. to escalate the stakes, or push the character towards catastrophe). The tragic endings of stories written with Freytag in mind are substantive and impactful — not just sadness for sadness’ sake.

Now that you're a bona fide Freytag expert, check out the rest of the posts in our guide for more insight into the wonderful world of story structure.